In this essay I hope to provide those with little or no knowledge of karate-do, and in particular the Shito-ryu sect, with a brief summary of events, places and key people who contributed to its development and ultimately its journey from a plebian art of self defense to a world wide phenomenon. It is by no means a detailed account and is only intended as a pre cursor for those who wish to know more. It is my hope then that those who read this modest essay will use it as a starting point and, coupled with the references listed below, will provide many hours of interesting reading and study on a fascinating story told by much better scholars and martial artists than myself. To use a quote from one such scholar and probably the most famous karate master, Funakoshi Sensei, ‘To search for the old is to understand the new’.

In this essay I hope to provide those with little or no knowledge of karate-do, and in particular the Shito-ryu sect, with a brief summary of events, places and key people who contributed to its development and ultimately its journey from a plebian art of self defense to a world wide phenomenon. It is by no means a detailed account and is only intended as a pre cursor for those who wish to know more. It is my hope then that those who read this modest essay will use it as a starting point and, coupled with the references listed below, will provide many hours of interesting reading and study on a fascinating story told by much better scholars and martial artists than myself. To use a quote from one such scholar and probably the most famous karate master, Funakoshi Sensei, ‘To search for the old is to understand the new’.

Shito-ryu (she-tou-ree-yu) is one of four major styles of karate developed in Japan. Since karate’s introduction to Japan’s mainland, largely during the Taisho period (1912-1926), karate has grown in popularity, not only in Japan but across the world. Its origins however, are deeply embedded in the tiny island of Okinawa (O-kee-na-wa ), the largest island in the Ryukyu Archipelago. Situated like a string of pearls stretching across the East China Sea, Okinawa lies approximately half way along a span of 1000km between the south coast of Kyushu (one of four islands that make up Japan’s mainland), and Taiwan which straddles the Tropic of Cancer.

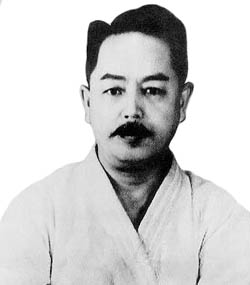

It was in Shuri, the ancient capital of Okinawa, that the founder of Shito-ryu karate, Kenwa Mabuni was born in 1889. A descendant of a distinguished warrior class, the young Mabuni, a sickly child, longed to possess the physical strength and fighting spirit of his ancestors. In 1902, aged 13 Mabuni was introduced to a well known exponent of Toudi-jutsu, the term given to the combat system of the day, Master Yasutsune ‘Ankho’ Itosu.

Master Itosu (b.1832 - 1915) was born and lived in Shuri, not far from the Mabuni household, and Mabuni trained everyday with the great master until enrolling into Okinawa’s First Middle School. During these years Mabuni continued his study of Toudi under Master Hanashiro Chomo (b.1869 - 1945). Historically, training in Toudi was always taught in private, in a secluded garden or room and only to those introduced to the Master by a good friend or family member. However, Master Itosu, a student of Grand Master, Sokon Matsumura, was instrumental in introducing karate into the Okinawan physical education school syllabus and did much to promote the growth and benefits of Toudi.

In 1910, at the age of 20, Kenwa Mabuni was introduced by his friend Chojun Miyagi (1888 – 1953), to another well known master of Toudi, Master Higashionna Kanryo (b. 1853 - 1916). Master Higashionna lived in Naha and although his style of Toudi differed from that taught by Master Itosu, Mabuni was acutely aware of its power and advantages in certain combative situations. Greatly enthused by the master’s alternative methods and techniques, Mabuni studied with great focus and passion. However, it was to be a short lived relationship as Mabuni would be called away to serve his 2 year national service after only a year of study with Higashionna. Much of what Mabuni learned about Higashionna’s methods were taught him by his friend and long time student of Higashionna, Miyagi Chojun.

On completion of his national service, aged 23, Mabuni embarked on a career in law enforcement and joined the police force. Excelling in his profession he was later promoted to detective and moved to the city of Naha. During this time Mabuni’s work would take him all over the island and into contact with a number of prominent martial artists including another great expert, Seisho Aragaki (1840 – 1920). A former teacher to Higashionna, and a man of great authority in ‘Te’ and ‘Kobudo’, (Kou-boo-dou, traditional Okinawan weaponry) Master Aragaki taught Mabuni several kata including Unshu, Niseishi and Sochin as well as Bo (6’ staff) and Sai (metal truncheon).

In 1927, Mabuni and friend Chojun Miyagi (founder of Goju-ryu) were invited to demonstrate their art to a special guest and fellow martial artist from the mainland, Dr. Jigoro Kano. Dr. Kano, the founder of Judo (joo-dou, ‘the gentle way’) had visited Okinawa twice previously but had never witnessed its indigenous fighting system. Keen to impress upon their special guest the art’s Okinawan heritage, the generic term, ‘Toudi’ (‘Chinese Hand’) was instead substituted by the terms Shuri-te, Naha-te and Tomori-te after the villages and towns where they developed. This better served to strengthen Toudi as an Okinawan art rather than highlight its Chinese origins.

Because the Okinawan Board of Education were organising the event, they expressed a wish that kata’s Pinan and Naifanchin (Heian and Naihanchi in mainland dialect) should be performed as these kata formed part of the Okinawan physical education syllabus, as introduced by Itosu sensei almost two decades previous. Though happy to oblige, Mabuni, knowing Dr. Kano’s immense political power and contacts could greatly assist in the growth and popularity of Toudi, felt this somewhat elementary performance might do Toudi more harm than good. Mabuni therefore asked Dr. Kano to attend a second demonstration the following day. Having agreed, Dr. Kano was met the following morning by a number of senior exponents, including Masters Yabu, Hanashiro, Kyan, Miyagi and Mabuni. This time the more advanced kata, techniques and applications were shown with great vigour and proficiency.

Impressed by the performances of the Toudi masters, Dr. Kano suggested that both Miyagi and Mabuni travel to the mainland to demonstrate their disciplines. Though many credit Funakoshi Gichin, a fellow student of Master Itosu and before that, Azato and Sokon Matsumura, with introducing Toudi to mainland Japan, it is more likely that a number of Okinawan Toudi exponents visited or settled in various parts of the mainland during the first thirty years of the 20th century, and subsequently began to teach their art. Among them another legendary and somewhat controversial Toudi master, Choki Motobu (1870 - 1944).

In 1928, Mabuni joined these Toudi pioneers and, having taken early retirement from the police department, travelled to Tokyo with his friend Chojun Miyagi. Meeting with friends Mr. Funakoshi and Dr. Kano, Mabuni and Miyagi were assisted in securing a number of opportunities to demonstrate their skills before the Japanese people and quickly realised there was a growing interest and enthusiasm for the Okinawan art and with it, a need for experts such as themselves to promote and teach Toudi, but not in private or seclusion as in previous times in Okinawa, but instead in an open and public way and to anyone who expressed a genuine interest regardless of class or position.

During these early years Mabuni and Miyagi met many interested individuals and soon began to attract their own followers and establish their own clubs. Out of respect for his friend Master Funakoshi who had previously established himself in Tokyo, Mabuni decided to settle in Osaka, a large port situated west, southwest of Tokyo, and later in the nearby ancient capital, Kyoto around 35 miles north east of Osaka. One of his closest friends and senior students was Konishi Yasuhiro. Konishi would often accompany Mabuni on his trips and the Konishi family would often look after Mabuni’s son, Kenei while his father travelled.

On one such trip Konishi accompanied Mabuni south of Osaka to meet with a fellow Okinawan, Master Uechi, founder of Uechi-ryu. Mabuni, unlike a number of his peers or masters did not study direct from the Chinese and was keen to learn as much about Chinese methods, techniques and tactics. Konishi later wrote that it was this meeting that inspired Mabuni’s kata ‘Shinpa’ (mind wave) which represented the defensive techniques used in the Fujian tiger boxing and Fujian dog boxing studied by Master Uechi during his years in Fuzhou, China. Mabuni’s eclectic knowledge and understanding of Toudi-jutsu earned him much acclaim particularly in the Kansai region where his style was referred to as ‘Hanko-ryu’, half hard style, or, in the Kanto region, simply ‘Mabuni-ryu’. Despite his popularity Mabuni never cashed in on his success and remained modest in every way.

In 1933 Toudi-jutsu was accepted by the Okinawan branch of the Dai Nippon Butoku-kai located in Naha and later that same year was accepted as a Japanese Budo (warrior way). The following year Mabuni named his interpretation of Toudi-jutsu ‘Shi-Tou-Ryu’ in honour of his first two principle teachers, Itosu and Higashionna. He did this by taking the first character of each of his master’s names, Ito-su ( ? also pronounced Shi) and Higashi-onna (also pronounced Tou). A year later, Mabuni Sensei opened his own dojo in Osaka and named it ‘Youshukan’ (apparently the name of a school he attended in Okinawa). In 1939 Mabuni registered Shito-ryu with the Dai Nippon Butoku-kai. By this time the more Japanese friendly term ‘karate-do’ - the Way of the Empty Hand, replaced Toudi-jutsu - Art of Chinese Hand. The suffix ‘do’ served to heighten karate’s standing in Japanese society, which sought a more spiritual way to develop the human character, a point of contention between some conservatives who remained in Okinawa and those seeking to promote the art and all it had to offer, to the Japanese.

Having been accepted into the Dia Nippon Butoku-kai, more changes were to follow. As karate began to develop and more clubs opened, it became apparent that the lack of standardised teaching methods, poor codes of conduct and a general lack of organisation were regarded as detrimental to the growth and development of karate-do. To remedy matters the Butoku-kai looked to the Budo systems it had developed before and using Dr. Kano’s Judo as a template, introduced the Dan / Kyu ranking system together with the white, cotton training uniform, ‘Dou-gi’ and coloured belts to denote proficiency. Initially there were only three colours of belt, (obi - o'bee) white for beginners, brown for intermediates and black for more advanced practitioners. Today however, many more colours are used, often one for each kyu level.

Other implementations included a unified teaching curriculum together with recognised teaching licences, in order to better evaluate the growing number of instructors. Regular exams were also introduced with a standardised system of evaluating both students and teachers. The first Shihan (master teacher) titles, started with: Renshi – well trained/skilled expert, Kyoshi – teaching expert, and the highest level, Hanshi – model teacher / expert teacher by example. These titles are still used today in many schools of karate-do.

Master Mabuni, having spent a life time studying Toudi, its origins in all its variations, amassed a wealth of knowledge unsurpassed by any of his peers. To his credit, the Shito-Ryu sect of modern day karate-do has over 50 kata, more than double the number practised by other schools. Because of his interest in Okinawan weaponry, which a number of masters whose guidance Mabuni sought also practiced, Shito-Ryu also prides itself with a large fraternity of Kobudo-ka (weapon practitioners).

The symbol used by the Shito-ryu association, Shito-Kai is the Mabuni family crest or mon. It is said that the circle is representative of ‘wa’ - harmony. And that the straight lines within the circle, closely resemble the Japanese characters for a person, and can be interpreted as ‘people coming together in harmony’. A fitting legacy for many thousands of men, women and children, who now practice the Shito-ryu karate-do left us by Master Kenwa Mabuni and those who helped, guided and supported him. Kenwa Mabuni died in 1952, and was succeeded by his sons Ken-ei and Kenzo. Kenzo Mabuni died in 26th June, 2005, and was succeeded by his daughter Tsukasa Mabuni. Ken-ei Mabuni, 2nd Soke (Head of Shitoryu) was made Governer of the World Shitoryu Karatedo Federation and now, in his nineties, still continues to practice and promote his fathers legacy to the world of karate-do.

The symbol used by the Shito-ryu association, Shito-Kai is the Mabuni family crest or mon. It is said that the circle is representative of ‘wa’ - harmony. And that the straight lines within the circle, closely resemble the Japanese characters for a person, and can be interpreted as ‘people coming together in harmony’. A fitting legacy for many thousands of men, women and children, who now practice the Shito-ryu karate-do left us by Master Kenwa Mabuni and those who helped, guided and supported him. Kenwa Mabuni died in 1952, and was succeeded by his sons Ken-ei and Kenzo. Kenzo Mabuni died in 26th June, 2005, and was succeeded by his daughter Tsukasa Mabuni. Ken-ei Mabuni, 2nd Soke (Head of Shitoryu) was made Governer of the World Shitoryu Karatedo Federation and now, in his nineties, still continues to practice and promote his fathers legacy to the world of karate-do.

Customer Reviews

I joined this great club in my mid 50's, having never done martial arts before. 5 years later I achieved my black belt! Karate has developed my fitnes... Read More

Mr Paul Drake

Come to SMA for the most friendly karate club experience possible. Adults, teenagers and younger children are all made to feel extremely welcome from... Read More

Pete Hayes

Over the years I've tried a few martial arts but I have never enjoyed learning a new skill as much as with SMA! The camaraderie and excellent teaching... Read More

Jim Jervis

Friendships, confidence, discipline, respect for self and others. They always want to train and lessons are fun and stimulating. Brian and Dona create... Read More

Mrs. Jane Saysom

Corey and I have been training for just over 2 years with Samurai Martial Arts. We have found the club to be very welcoming and have made some good fr... Read More

Mr Tony Dix and son, Corey

A truly wonderful Karate school that has taught my two children over the last few years, and I would strongly recommend this academy to anyone. A big... Read More

Cynthia Kong - Cheltenham

Both our sons train with SMA and we strongly believe that participating in karate has provided benefits beyond fitness and self-defence. With our olde... Read More